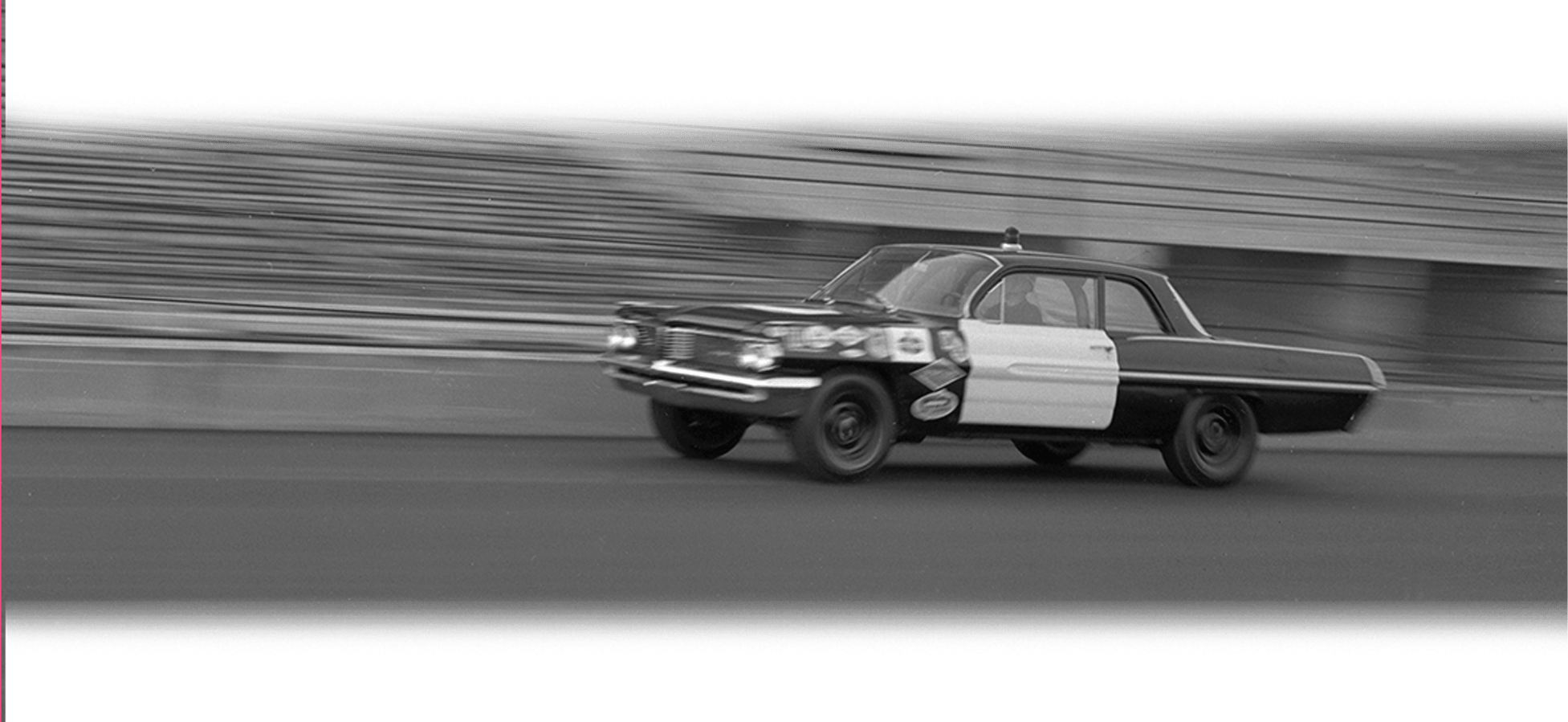

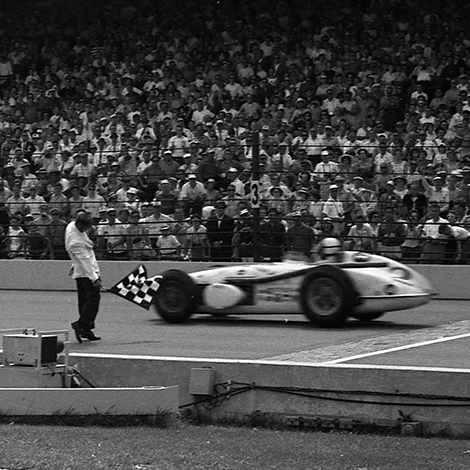

Taking the checkered flag in absolutely appalling conditions at 3 p.m. on the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1961, a Police Enforcer version of the Pontiac Catalina successfully completed a 24-hour run at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

1961 STOCK CAR TEST– 60 YEARS

The Police Enforcer had covered a distance of 2,586.878 miles at an average speed of 107.787 mph. A few ticks of the watch later, a second Pontiac—a more standard Catalina—roared past the start/finish line, this one having logged 2,576.241 miles at an average of 107.343 mph.

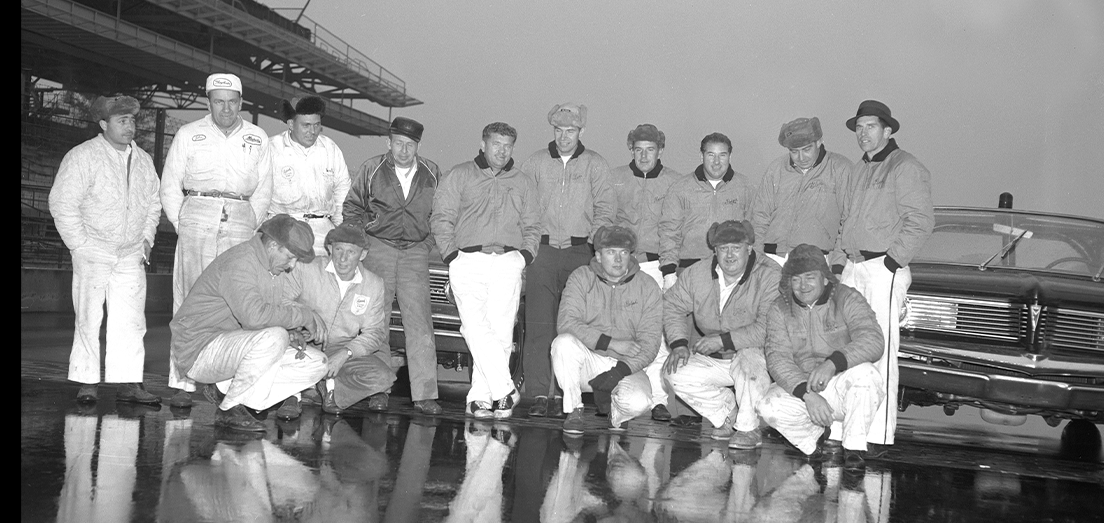

It was the biggest demonstration by NASCAR drivers and stock cars at the famed Speedway in its 50 years of operation, offering future NASCAR Hall of Fame drivers and mechanics an opportunity to show their skills at Indianapolis.

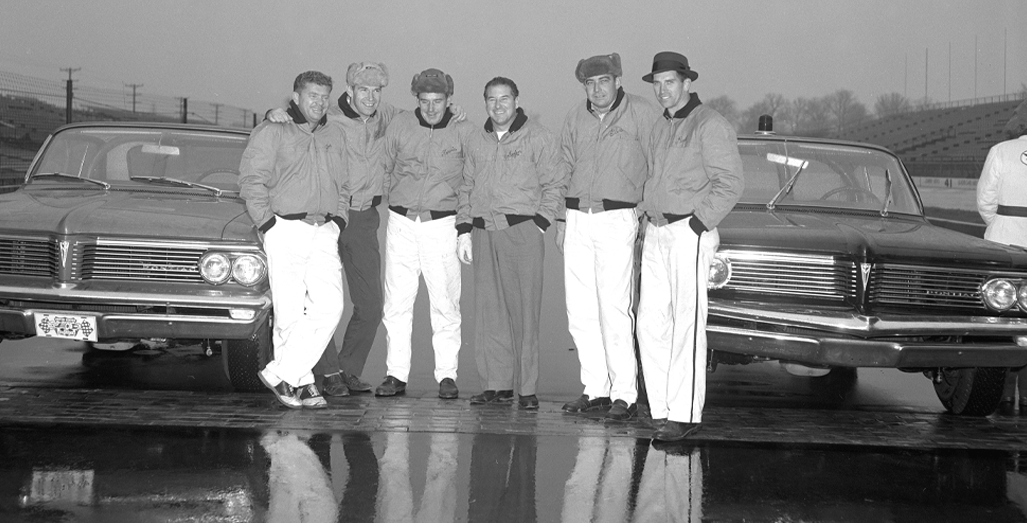

Both cars were prepared by Nichels Engineering of Highland, Indiana, and were shared by the same six drivers, three coming from the ranks of NASCAR and three from the United States Auto Club, the sanctioning body which supervised the run.

Representing NASCAR were then-current Daytona 500 winner Marvin Panch, eventual two-time NASCAR champion Joe Weatherly and one of the true giants of the sport, the legendary Glenn "Fireball" Roberts.

Representing USAC were Rodger Ward, who had finished first, second and third in the three most recent Indianapolis 500s; Paul Goldsmith, third-place finisher in the 1960 Indianapolis 500, who had just wrapped up his first of two straight USAC Stock Car championships; and a third "500" driver, Len Sutton, winner in recent weeks of two of the last four USAC stock car features of the season.

It was somewhat ironic that the two drivers who happened to be on the track when the checker was waved—Ward in the Police Enforcer and Sutton in the Catalina—would end up being the one–two finishers as teammates for Leader Card Racers in the 1962 "500," six months later.

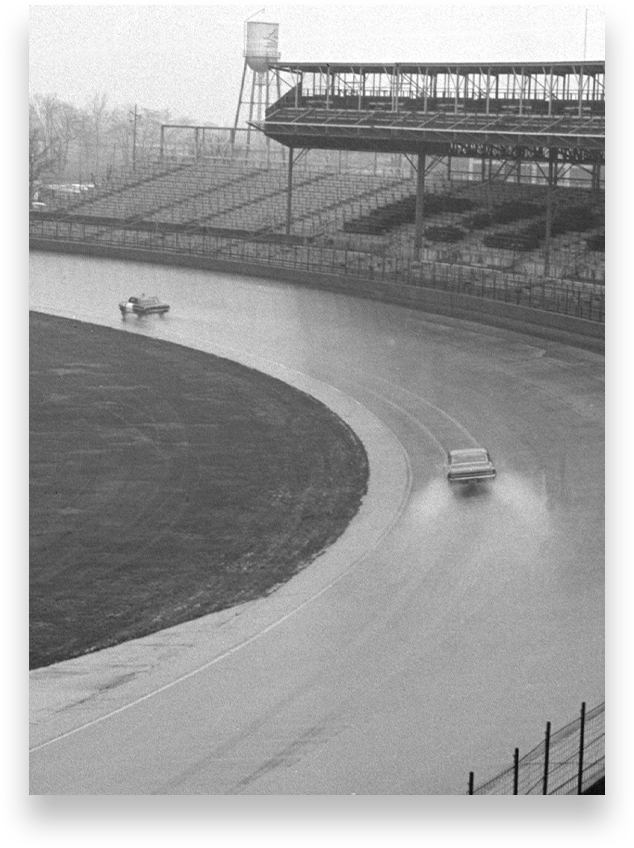

The six drivers, who served at least two shifts each in both cars, had to contend with rain for much of the final 11 hours. They were also the first drivers to lap the track in its new form, the paving over of the final 600-plus yards of bricks on the main straight having taken place only six weeks earlier.

In fact, with Panch, Weatherly and Goldsmith all on hand, it meant that each of the top three finishers in February's Daytona 500 was represented.

USAC Director of Competition Henry Banks conducted a draw in the press room beneath the main straight grandstands to determine the order in which each driver would take a shift.

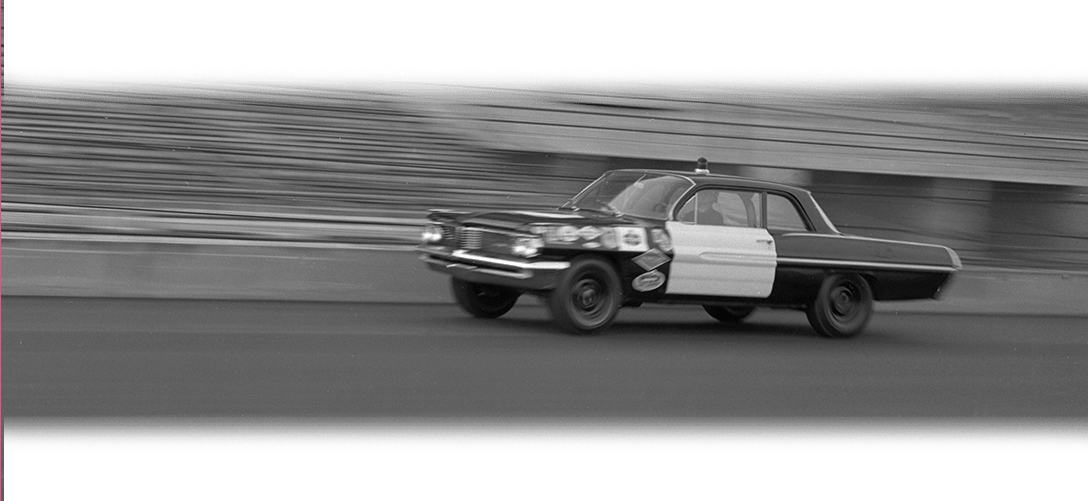

The single beacon "bubble-gum machine" light on the car's roof was more than just for show. Not only was it hooked up, but it was activated throughout the entire night in order for the holder of the pit board to be able to identify which car was approaching.

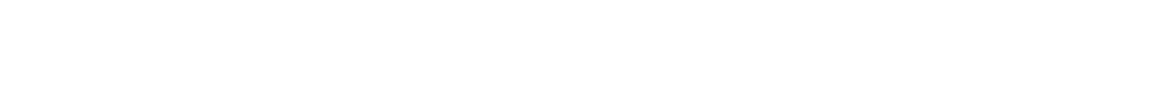

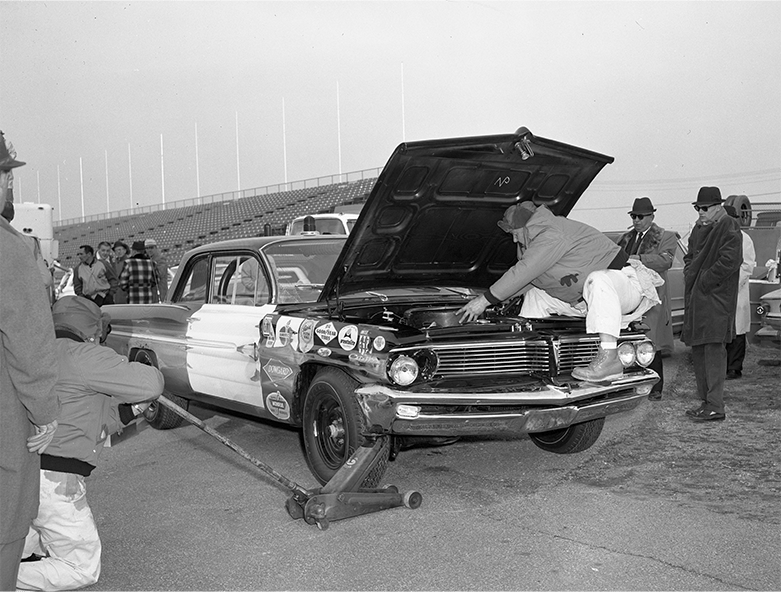

It didn't take long for the single-lap mark of 117.832 mph by Mantz in 1956 to topple. On only the second lap of the run, Goldsmith turned 118.953 mph with the Enforcer. He soon upped that to 120.822 mph and continued in that range for the first 50 miles until brushing the outside wall out of Turn 4 on his 21st lap.

Just under five minutes were lost in the pits while the right-side sheet metal was hammered out, but nothing was forfeited in the speed department, Roberts later taking over the car and squeezing out a lap at 122.132 mph, the fastest by anyone throughout the entire exercise. Notably, both Roberts and Sutton were credited with laps at 121 mph in the dark, no less.

The Speedway's 500-mile record for stock cars also was broken along the way, raised to 113.292 mph by the quartet of Panch, Sutton, Roberts and Goldsmith in the Catalina. This exceeded the 111.916 mph established in 1956 with a Ford shared by Johnny Mantz and Chuck Stevenson.

The Police Enforcer broke the 24-hour record by over 400 miles, the previous mark having been 2,157.5 miles (average speed, 89.89 mph) set with a Chrysler shared by Tony Bettenhausen, Pat O'Connor and Bill Taylor in 1953.

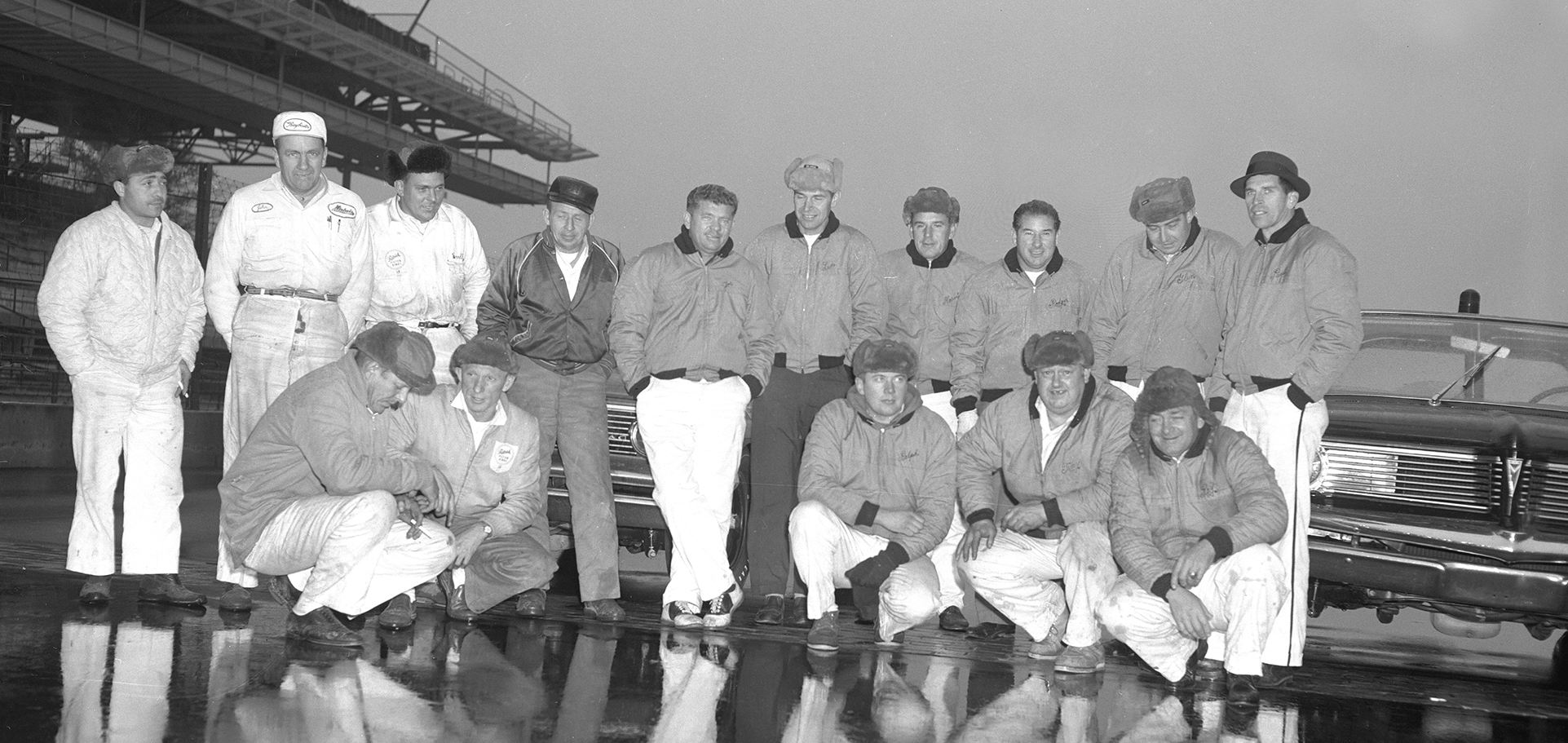

Owens had been runner-up to Lee Petty in the NASCAR championship two years earlier and had won four races in the most recent season. It was said that Worley and Moore, who supervised the fuel and tire stops, went sleepless for 36 hours.

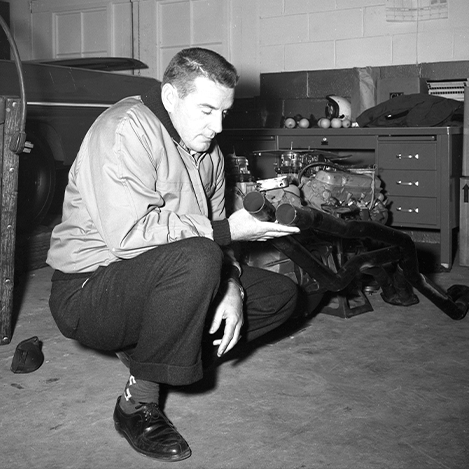

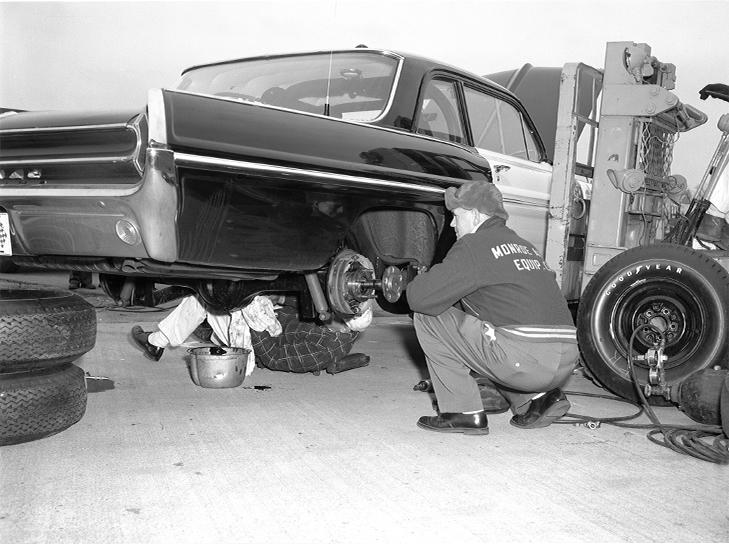

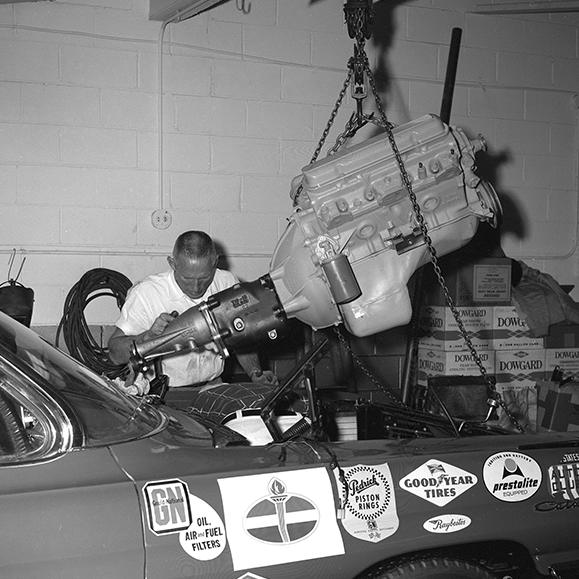

Ray Nichels had an all-star cast on hand, headed up by NASCAR's Bud Moore and by Dale "Tiny" Worley, a member of the winning "500" crew in 1951, '57 and '58. Also heavily involved was NASCAR driver-turned-car owner Everett "Cotton" Owens, and the legendary Henry "Smokey" Yunick.

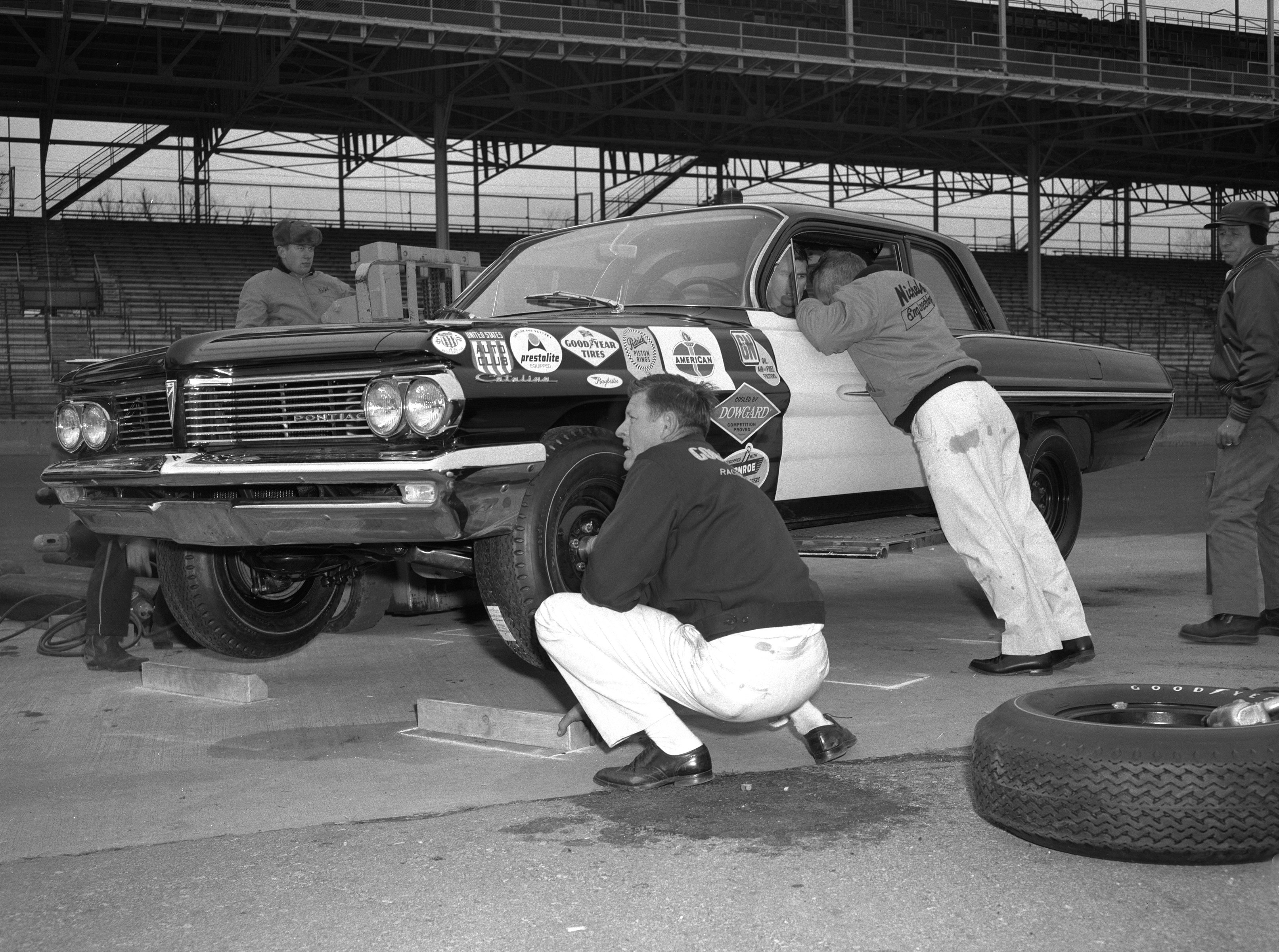

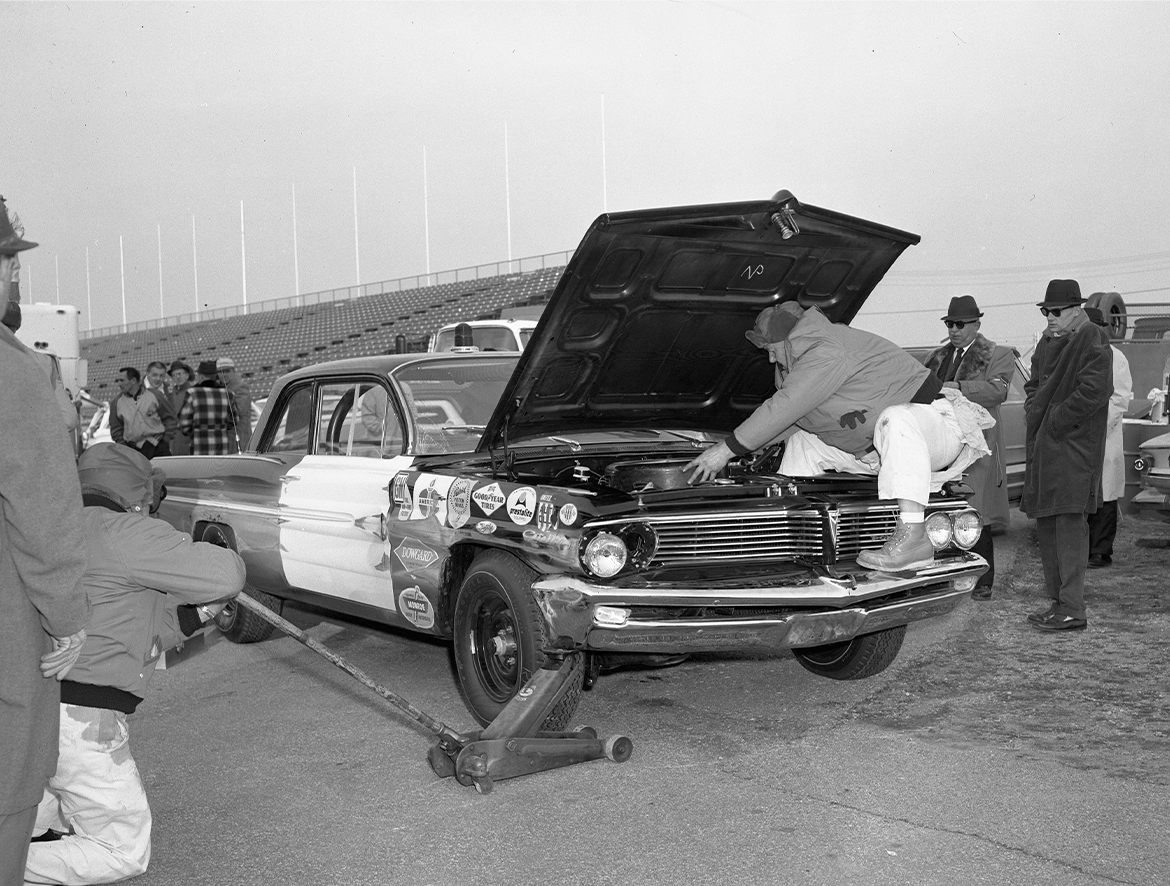

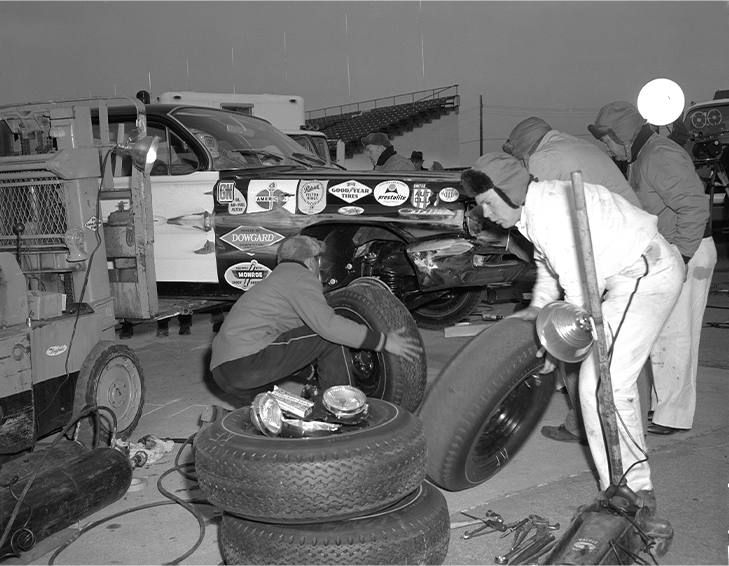

Each pit stop was quite a production. Rather than use the regular pits, Nichels elected to set up on the track, just at the entrance to Turn 1. For some reason it was decided that instead of using jacks to raise the cars, the job would be performed by a forklift.

During the night, many of the crew members would attempt to keep warm and/or take a nap in one of the half-dozen or so vehicles parked in the immediate area. Whenever a pit stop was about to take place, blasts from several car horns would alert everyone and three or four searchlights would be turned on.

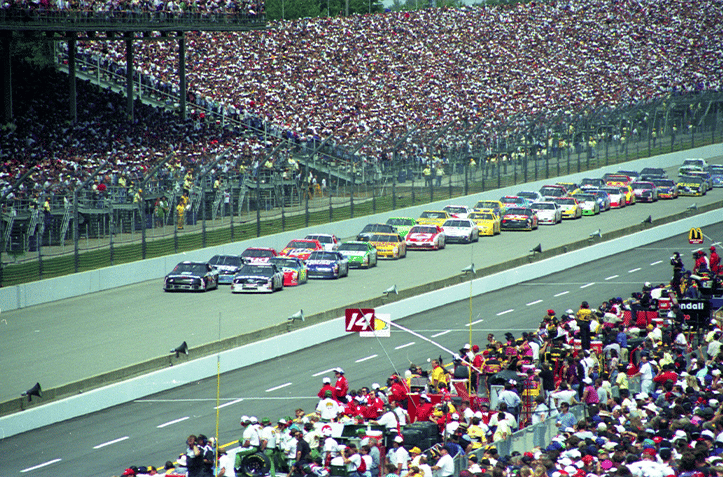

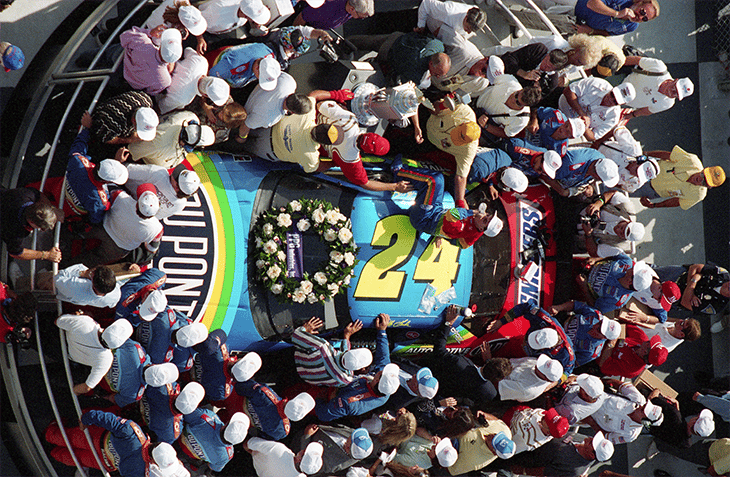

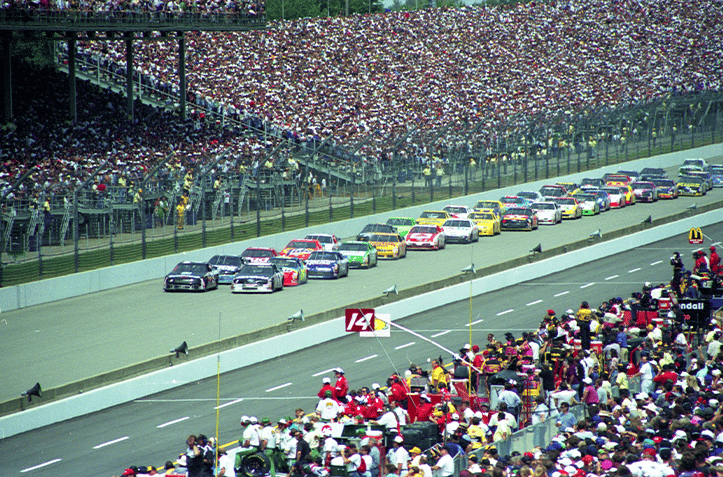

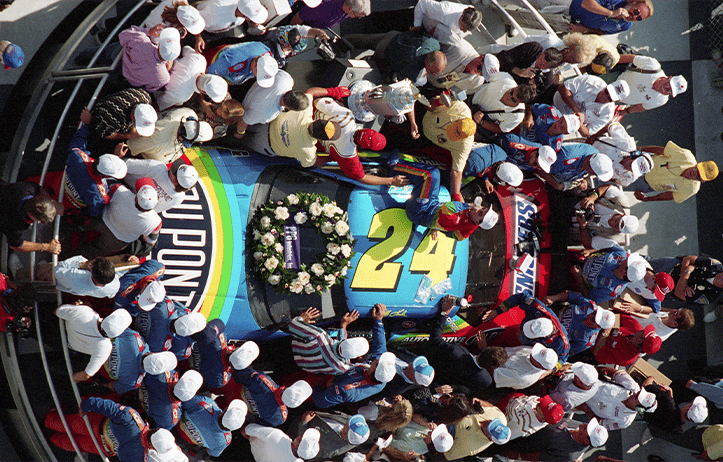

More than two years later, on Aug. 6, 1994, the inaugural Brickyard 400 was held in front of a sellout crowd estimated at 250,000. Adopted Hoosier Jeff Gordon won in front of the crowd that holds the record as the largest-attended NASCAR race in history.

With the use of two-way radios still a couple of decades in the future, pit boards were the standard form of communication. An effort was made to display at least something on virtually every one of the 2,065 laps throughout the 24 hours in order to keep the drivers alert. On one lap, in an attempt to avoid the monotony, Worley needled Ward with the message: "Foyt—5 secs."

At least seven accessory companies helped underwrite the run, each using it to vigorously test their products. Thus, more than half a century after the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had been built as a proving ground it was still being utilized for the very purposes originally envisioned by its founders.

It was the biggest stock car test to date at the famed 2.5-mile oval, and it held that title for more than 30 years until NASCAR returned to the Speedway in 1992 for a tire test, the first official NASCAR test in the racetrack’s history.

Rusty Wallace, Dale Earnhardt, Ricky Rudd, Mark Martin, Bill Elliott, Darrell Waltrip, Ernie Irvan, Davey Allison and Kyle Petty drove their stock cars around the circuit June 22-23. The top speed was 168.767 mph by Elliott on June 23.

Thousands of fans lined 16th Street as the NASCAR haulers arrived late the evening of June 21 from a race at Michigan International Speedway, showing just how high the excitement level was to see NASCAR stock cars in Indianapolis.

As the story goes, Bill France Jr. and Tony George were sitting in the grandstands during the test. At a certain point, the two reached over and shook hands, indicating that a deal had just been made, if not on paper yet, to host a NASCAR race at the Racing Capital of the World.

WHERE TRADITION NEVER STOPS

1961 STOCK CAR TEST– 60 YEARS

In fact, with Panch, Weatherly and Goldsmith all on hand, it meant that each of the top three finishers in February's Daytona 500 was represented.

USAC Director of Competition Henry Banks conducted a draw in the press room beneath the main straight grandstands to determine the order in which each driver would take a shift.

It was somewhat ironic that the two drivers who happened to be on the track when the checker was waved—Ward in the Police Enforcer and Sutton in the Catalina—would end up being the one–two finishers as teammates for Leader Card Racers in the 1962 "500," six months later.

The six drivers, who served at least two shifts each in both cars, had to contend with rain for much of the final 11 hours. They were also the first drivers to lap the track in its new form, the paving over of the final 600-plus yards of bricks on the main straight having taken place only six weeks earlier.

The Police Enforcer broke the 24-hour record by over 400 miles, the previous mark having been 2,157.5 miles (average speed, 89.89 mph) set with a Chrysler shared by Tony Bettenhausen, Pat O'Connor and Bill Taylor in 1953.

The Speedway's 500-mile record for stock cars also was broken along the way, raised to 113.292 mph by the quartet of Panch, Sutton, Roberts and Goldsmith in the Catalina. This exceeded the 111.916 mph established in 1956 with a Ford shared by Johnny Mantz and Chuck Stevenson.

It didn't take long for the single-lap mark of 117.832 mph by Mantz in 1956 to topple. On only the second lap of the run, Goldsmith turned 118.953 mph with the Enforcer. He soon upped that to 120.822 mph and continued in that range for the first 50 miles until brushing the outside wall out of Turn 4 on his 21st lap.

Just under five minutes were lost in the pits while the right-side sheet metal was hammered out, but nothing was forfeited in the speed department, Roberts later taking over the car and squeezing out a lap at 122.132 mph, the fastest by anyone throughout the entire exercise. Notably, both Roberts and Sutton were credited with laps at 121 mph in the dark, no less.

The single beacon "bubble-gum machine" light on the car's roof was more than just for show. Not only was it hooked up, but it was activated throughout the entire night in order for the holder of the pit board to be able to identify which car was approaching.

Ray Nichels had an all-star cast on hand, headed up by NASCAR's Bud Moore and by Dale "Tiny" Worley, a member of the winning "500" crew in 1951, '57 and '58. Also heavily involved was NASCAR driver-turned-car owner Everett "Cotton" Owens, and the legendary Henry "Smokey" Yunick.

Owens had been runner-up to Lee Petty in the NASCAR championship two years earlier and had won four races in the most recent season. It was said that Worley and Moore, who supervised the fuel and tire stops, went sleepless for 36 hours.

Each pit stop was quite a production. Rather than use the regular pits, Nichels elected to set up on the track, just at the entrance to Turn 1. For some reason it was decided that instead of using jacks to raise the cars, the job would be performed by a forklift.

Each pit stop was quite a production. Rather than use the regular pits, Nichels elected to set up on the track, just at the entrance to Turn 1. For some reason it was decided that instead of using jacks to raise the cars, the job would be performed by a forklift.

With the use of two-way radios still a couple of decades in the future, pit boards were the standard form of communication. An effort was made to display at least something on virtually every one of the 2,065 laps throughout the 24 hours in order to keep the drivers alert. On one lap, in an attempt to avoid the monotony, Worley needled Ward with the message: "Foyt—5 secs."

At least seven accessory companies helped underwrite the run, each using it to vigorously test their products. Thus, more than half a century after the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had been built as a proving ground it was still being utilized for the very purposes originally envisioned by its founders.

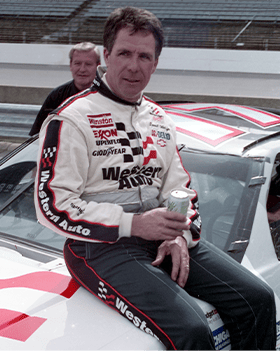

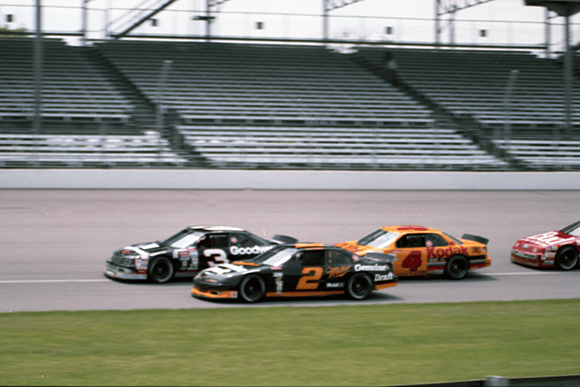

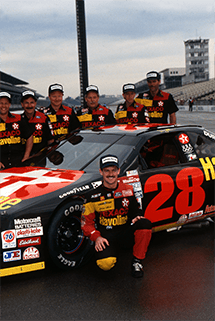

It was the biggest stock car test to date at the famed 2.5-mile oval, and it held that title for more than 30 years until NASCAR returned to the Speedway in 1992 for a tire test, the first official NASCAR test in the racetrack’s history.

Rusty Wallace, Dale Earnhardt, Ricky Rudd, Mark Martin, Bill Elliott, Darrell Waltrip, Ernie Irvan, Davey Allison and Kyle Petty drove their stock cars around the circuit June 22-23. The top speed was 168.767 mph by Elliott on June 23.

Thousands of fans lined 16th Street as the NASCAR haulers arrived late the evening of June 21 from a race at Michigan International Speedway, showing just how high the excitement level was to see NASCAR stock cars in Indianapolis.

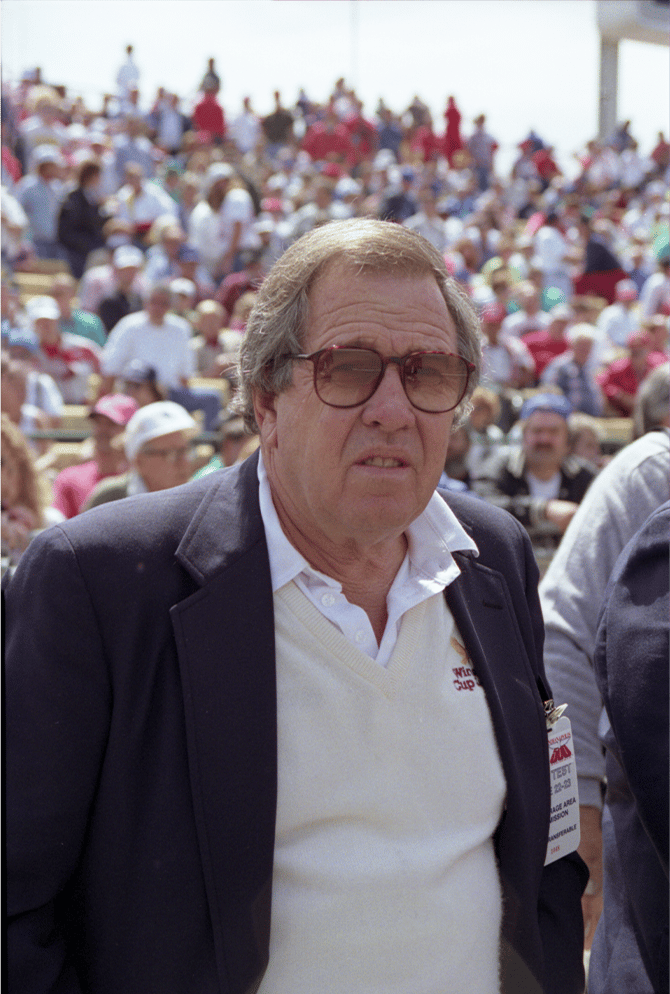

As the story goes, Bill France Jr. and Tony George were sitting in the grandstands during the test. At a certain point, the two reached over and shook hands, indicating that a deal had just been made, if not on paper yet, to host a NASCAR race at the Racing Capital of the World.

More than two years later, on Aug. 6, 1994, the inaugural Brickyard 400 was held in front of a sellout crowd estimated at 250,000. Adopted Hoosier Jeff Gordon won in front of the crowd that holds the record as the largest-attended NASCAR race in history.

Taking the checkered flag in absolutely appalling conditions at 3 p.m. on the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1961, a Police Enforcer version of the Pontiac Catalina successfully completed a 24-hour run at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

The Police Enforcer had covered a distance of 2,586.878 miles at an average speed of 107.787 mph.

A few ticks of the watch later, a second Pontiac—a more standard Catalina—roared past the start/finish line, this one having logged 2,576.241 miles at an average of 107.343 mph.

It was the biggest demonstration by NASCAR drivers and stock cars at the famed Speedway in its 50 years of operation, offering future NASCAR Hall of Fame drivers and mechanics an opportunity to show their skills at Indianapolis.

Both cars were prepared by Nichels Engineering of Highland, Indiana, and were shared by the same six drivers, three coming from the ranks of NASCAR and three from the United States Auto Club, the sanctioning body which supervised the run.

Representing USAC were Rodger Ward, who had finished first, second and third in the three most recent Indianapolis 500s; Paul Goldsmith, third-place finisher in the 1960 Indianapolis 500, who had just wrapped up his first of two straight USAC Stock Car championships; and a third "500" driver, Len Sutton, winner in recent weeks of two of the last four USAC stock car features of the season.

Representing NASCAR were then-current Daytona 500 winner Marvin Panch, eventual two-time NASCAR champion Joe Weatherly, and one of the true giants of the sport, the legendary Glenn "Fireball" Roberts.